People in tales

People in tales

[Khon Nai Nithan – Korn Siriwattano]

[คนในนิทาน โดย กร ศิริวัฒโณ]

The “erotic” label works wonders. A year and a half after its publication, this “erotic novel harking back to the agricultural society” is in its third edition. The jacket has mercifully dropped the initial Thaiglish subtitle of “People in story”.

This is a set of tales behind tales, using those of the Ramayana to back up and sort of justify the contemporary one: if the gods can do it to the titillation of the plebs, why can’t mere mortals without feeling shame and earning opprobrium and ostracism from the same hoi polloi? The “it” in question is making love to animals, which the ageing head of the family indulges in, twice, with his fat female dog (and a sorry mess he makes of it each time). This puts him at the mercy of his first son-in-law, who demands and gets house and land and who will by and by also bed his mother-in-law (when his own wife is heavy with child) and, through a Trump-like liquid trick, his sister-in-law, otherwise married to a decent fisherman. The whole tale ends badly with cutlasses at work.

Even though there is no indication of which century all of these shenanigans take place, there are plenty of details on rural life in the South around the Songkhla Lake, with minimum usage of Southern Thai dialect. The author – a retired teacher and an excellent short-story writer – is careful not to be smutty, to the extent of calling the lingam chai yai (big man), jao tua yai (the big one) or even jom thep (supreme god) and the yoni nuan nong (little creamy). He also has the irritating habit of second-rate Thai writing to keep repeating qualifications, for instance, every time the unfortunate fisherman opens his mouth it is siang lek laem (with a high-pitched voice) or X phu sami (husband X), Y phu khuei (son-in-law Y) and so on.

By the way, there is no attempt to explain why the farmer has to avail himself of a dog rather than of his bossy wife, apart from pleading passing moments of aberration and the dark side in each of us.

Eroticism-wise, it would be tempting to say dismissively that this is fine for the prudish Thai market, but then only notches below the stylistic graces of ’Rong Wongsawan or the dense meanderings of The Story of Jan Darra.

Jomthian – 30.09.18

The setting Buddhist era and the recollection of the recollections of the cat Black Rose (or something to that effect)

The setting Buddhist era and the recollection of the recollections of the cat Black Rose (or something to that effect)

[Phutthasakkarat Atsadong Kap Songjam Khong Songjam Khong Maew Kulap Dam – Veeraporn Nitiprapha]

[พุทธศักราชอัสดงกับทรงจําของทรงจําของแมวกุหลาบดํา โดย วีรพร นิติประภา]

Congratulations, Ms Veeraphorn, you’ve come up with the longest, most idiotic title for a Thai novel, beating Arunwadi Arunmart’s 1997 Kan Lom Salai Khong Sathaban Khropkrua Thee Khwamrak Mai Art Yiaoya, which by the way made more sense than yours – and which you can find in French as La Voix du sang (2010).

I don’t know if I’m going to read and review this 420-page book chock-full of dictionary words, but I feel I must translate the author’s foreword, it’s so original and fanciful.

“Sure you did. You must have known a moment like that, when you wake up in the middle of the night after a storm. Everything is calm, still and quiet. You feel relaxed without knowing why as you take a deep breath, but before you can doze off again, lightning strikes deafeningly and then the rain pounds.

You must have gone through such a moment… Why wouldn’t you? Dancing frantically to excess until the song ends, and right then the light turns so bright it brings tears to your eyes… When the bar is closed, waiting for someone to phone… clenching the phone against your heart all evening to find that when it rings at midnight it’s some drunk who dialled a wrong number… Reading a novel until it comes to what you think is the best part and then turning the page only to find it was the last page.

Sure you did. You must have pestered no end your mother to have her buy you a cake only to find that the flavour you liked was sold out, and furthermore your mother bought the flavour you disliked most because that was all that was left, and after a long war lasting all morning you sat down there in the weak light of a candle above the dinner table, tolerating that confounded cake one mouthful at a time.

And then your life… you have never understood why you hate waking up in the dark, why you don’t dance, turn off the television early in the evening, have given up on cakes… don’t like novels and sometimes… once in a long while recollecting moments as tiny as particles of dust springing back and you can’t help laughing at yourself for having hoped… so very much, but many times you have already forgotten.

This is a novel written about the second between the third and fourth waves of the tsunami.

A second so fragile in between hopes.

Veeraporn Nitiprapha – October 2016”

Jomthian – 01-10-18

PS 05.10.18, 5 pm: Predictably enough, this novel has just received the 2018 SEA Write Award.

A drop of nectar in the tears

A drop of nectar in the tears The house in the mud

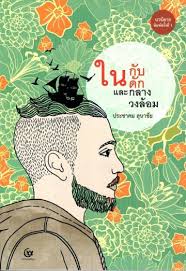

The house in the mud  Trapped and surrounded

Trapped and surrounded